MANILA. Dr. Joel Joseph S. Marciano Jr. speaks about Diwata 1, the Philippines’ first earth observation microsatellite, during the 20th Graciano Lopez Jaena Community Journalism Workshop on Science Journalism in UP Diliman, Quezon City. (Alex Tamayo)

MANILA. Dr. Joel Joseph S. Marciano Jr. speaks about Diwata 1, the Philippines’ first earth observation microsatellite, during the 20th Graciano Lopez Jaena Community Journalism Workshop on Science Journalism in UP Diliman, Quezon City. (Alex Tamayo)

How not to be a rocket scientist and still rock

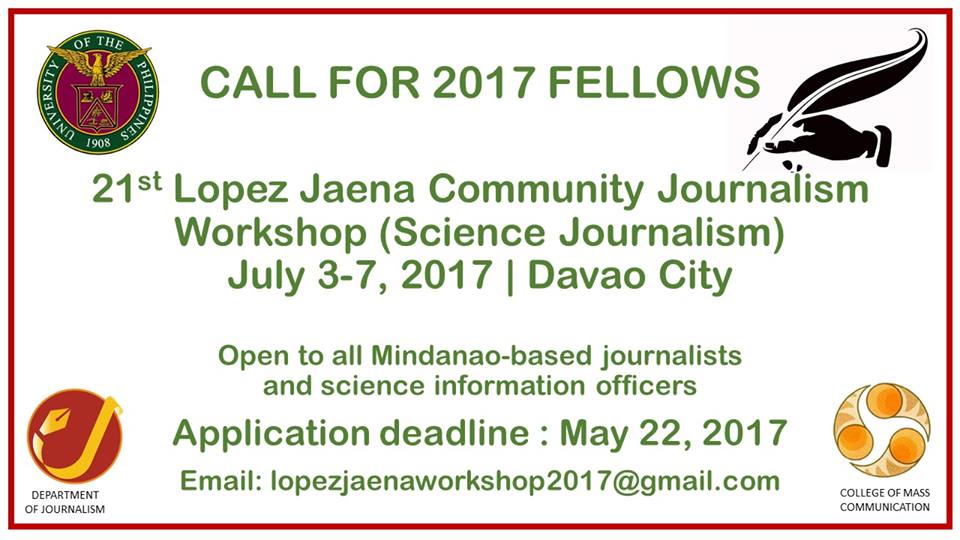

I have been blessed to join the 20th Graciano Lopez Jaena Community Journalism Workshop on Science Journalism which was organized by the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication Journalism Department from November 27 to December 2, 2016.

I am glad to share to you that the venue for this year’s seminar-workshop will be here in Davao City this July. Sharing to you Leia Castro-Margate’s story about the Philippine’s microsatellite. Leia is a colleague who won first prize for this article.

* * * * * *

MANILA. Dr. Joel Joseph S. Marciano Jr. speaks about Diwata 1, the Philippines’ first earth observation microsatellite, during the 20th Graciano Lopez Jaena Community Journalism Workshop on Science Journalism in UP Diliman, Quezon City. (Alex Tamayo)

“I am not a rocket scientist, I am an electrical engineer,” Marciano clarifies with emphasis before beginning his presentation on “Rocket Science” to fellows of the 20th Graciano Lopez Jaena Community Journalism Seminar Workshop on Science Journalism on November 29.

“Rocket Science”, as the fellows would jokingly remember hours after the mind-blowing presentation, refers to Marciano’s presentation on Diwata I, or the Philippines’s First Earth Observation Microsatellite.

Hearing the word “satellite” immediately evokes visions of outer space, of astronauts (or “Filipinauts”) gliding effortlessly in zero gravity, and a stern but geeky looking head scientist supervising all operations from the Earth station.

Marciano certainly looks the part of the head scientist, wise and stern looking at first glance, but the longer you watch and listen to him discuss the science behind space technology, the more you would behold him in a rock-star manner.

After finishing his BS Electrical Engineering degree at the University of the Philippines Diliman (UPD), Marciano said he planned to work at the then-emerging telecommunications company of Smart, but was convinced by a mentor to teach at UP instead. He never looked back.

He later took his PhD in Electrical Engineering and Telecommunications at the University of South Wales in Australia.

He is currently a Dado and Maria Banatao Professor of Electrical and Electronics Engineering at the College of Engineering at UPD, and acting director of the Advanced Science and Technology Institute of the UP Department of Science and Technology.

Building Diwata I started with a burning question: “Who knows how to build a satellite?”The search for Filipino experts yielded nothing. Marciano said, “No one knows how to build one.”

The better question came next in the form of a proposal: “Who would like to learn how to build the Philippine’s first Earth Observation microsatellite?”

Qualified Filipinos who wouldn’t jump at this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to trail blaze space-technology research in the country must be out of their minds.

Marciano was chosen to head the Philippines (PHL)-Microsat Program. He started putting together a team of very young and talented engineers, scientists and researchers from various fields.

“It’s a very daunting challenge. It requires a village to do something like this,” Marciano said. “Fortunately, I have been collaborating with a very good team.”

Backed by the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) and UP, the team tied up with experts from two universities in Japan: Tohoku and Hokkaido.

The Japanese have been in the space race for decades and the team saw it best to learn from people in the know.

Marciano went on to regale the journalism fellows about the science behind launching a satellite, the lessons and experiences they had on the field from the preparations made in the Philippines, the yearlong development of the test model and actual models of Diwata 1 in Japan, the launching of the satellite in the United States, to receiving the first photographs from space, and giving updates on the status of Diwata 2.

After his presentation, he was swamped with questions about Diwata 1 and 2, which he answered with every ease of an experienced front man. But asked how he feels about being in the forefront of Philippine Space Technology research, he gets stumped.

“That’s a good question, I haven’t really thought about it that much,” he said, while contemplating his answer to the question. Then he relayed how his children feel about him leading the program.

“My kids tell me they talked about Diwata 1 in school but they cannot brag about it because when they ask me questions about it I tell them it is top secret,” he added with a smile. “Maybe someday we will be in the textbooks.”

Even after accomplishing such astronomical feat, the Engineer shows no sign of stopping. He knows that Diwata 1 is only the beginning of more opportunities.

“The government needs help to develop space-science research,” he said. “It feels good to be contributing. I see myself as a provider of opportunities to younger people because I am in a position to connect the DOST to them.”

“Maybe space is not the ultimate destination, but along the way, we may discover where we want to go,” Marciano says on looking forward to the future.

After Diwata 1 and with Diwata 2 in the works by Filipino scientists, the question on “Who knows how to build a satellite?” will no longer be met with silence. But whether Marciano would be the first to raise his hand in assent would be uncertain, I suspect he would just be waiting and smiling in the background ready to roll—rock-star style.

No Comments